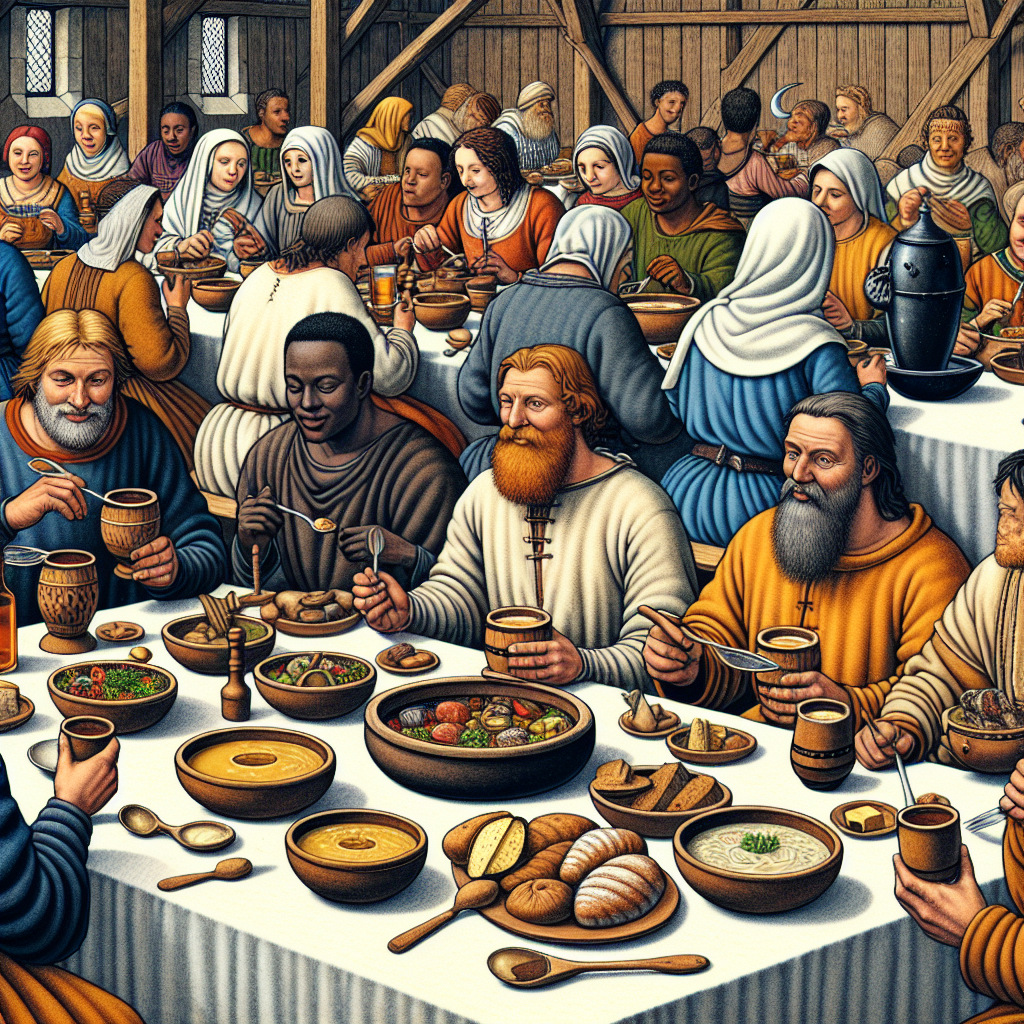

When most people picture medieval food, they imagine huge banquets, greasy roasted meats, and goblets overflowing with wine. Hollywood has painted a picture of feasting knights tearing into turkey legs and peasants gnawing on stale bread. But the truth about medieval diets is far more complex—and, in many ways, surprisingly balanced and regional. What people ate in the Middle Ages depended greatly on class, location, season, and religion, and their culinary habits reveal a fascinating story about how they lived, worked, and even thought about health.

For most of medieval Europe’s population—the peasants—the daily meal was built around grains. Bread was the cornerstone of the medieval diet, but not the soft, fluffy kind we know today. Instead, loaves were dense, dark, and made from barley, rye, or oats, since fine wheat was expensive and reserved for the upper classes. A typical peasant breakfast might consist of coarse bread soaked in ale or broth, while the evening meal (known as “supper”) could include pottage—a thick, hearty stew made from whatever vegetables, grains, and sometimes scraps of meat were available. It was a meal that changed with the seasons and whatever grew nearby.

Vegetables were more common than most assume. Onions, leeks, cabbage, turnips, and beans were staples in most medieval gardens. Peasants often ate more vegetables than meat simply because livestock was valuable alive—for milk, wool, and labor—rather than as food. Meat was eaten, but sparingly, often reserved for holidays or special gatherings. The rich, on the other hand, made meat a symbol of status. They enjoyed venison, boar, and game birds, all cooked with elaborate spices imported from as far as the Middle East. Spices like cinnamon, ginger, and cloves were used not only for flavor but as a display of wealth and connection to global trade routes.

One surprising fact is how religious life shaped medieval menus. The Christian calendar included numerous fasting days—sometimes up to half the year—when meat, dairy, and eggs were forbidden. This forced creativity in the kitchen, leading to an impressive array of “fish days.” Even people living far from the sea ate preserved or freshwater fish, such as herring, eel, or pike. Salted and dried fish became an entire trade network across Europe. In monasteries, fasting rules were especially strict, yet the monks’ diets were often healthier than those of the nobility, full of vegetables, grains, and fish rather than heavy meats and sauces.

Another forgotten feature of medieval eating habits is how they viewed food as medicine. The theory of the “four humors”—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—was central to medieval medicine, and foods were classified as hot, cold, moist, or dry. People believed eating the wrong “temperament” could throw their humors out of balance. For instance, pork was considered “moist and hot,” so it should be eaten with “cold” foods like apples to maintain harmony in the body. Meals were not just nourishment—they were part of a system of health management rooted in philosophy and belief.

The medieval drink of choice was not water, which was often unsafe to consume, but ale or small beer—a weak, fermented beverage low in alcohol and safer than untreated water. Wine was common in southern Europe and among the upper classes elsewhere, but most common folk brewed their own ale at home. Interestingly, dairy products like milk and butter were mostly eaten by peasants and monks; the wealthy considered them too rustic and preferred almond milk, an early plant-based alternative made from ground almonds and water.

Feasts did exist, of course, and they were spectacles of social order as much as gastronomy. Great lords and kings dined on peacocks, swans, or even porpoise, presented in elaborate displays. But these were rare occasions. The everyday medieval diet was practical, regional, and surprisingly plant-heavy. In fact, compared to the meat-heavy diets of modern times, the average peasant’s food—though limited and monotonous—was often less processed and closer to what we might now call “whole food.”

So, while the image of knights feasting in candlelit halls isn’t entirely wrong, it tells only a sliver of the story. Most medieval people ate humbler fare that reflected the rhythms of the land and the teachings of the Church. Their table was one of necessity, ingenuity, and balance—far removed from the greasy caricatures of legend. In understanding what they truly ate, we catch a glimpse not only of medieval cuisine but of a world where every bite was tied to faith, class, and the turning of the seasons.