When the Black Death swept across Europe in the mid-14th century, it killed an estimated one-third to half of the continent’s population — an unimaginable tragedy that reshaped nearly every aspect of life. But out of that devastation emerged profound changes that would lay the groundwork for the modern economic world. The plague was not only a catastrophe of human suffering; it was also a radical turning point that transformed labor, wealth, and power in ways still felt today.

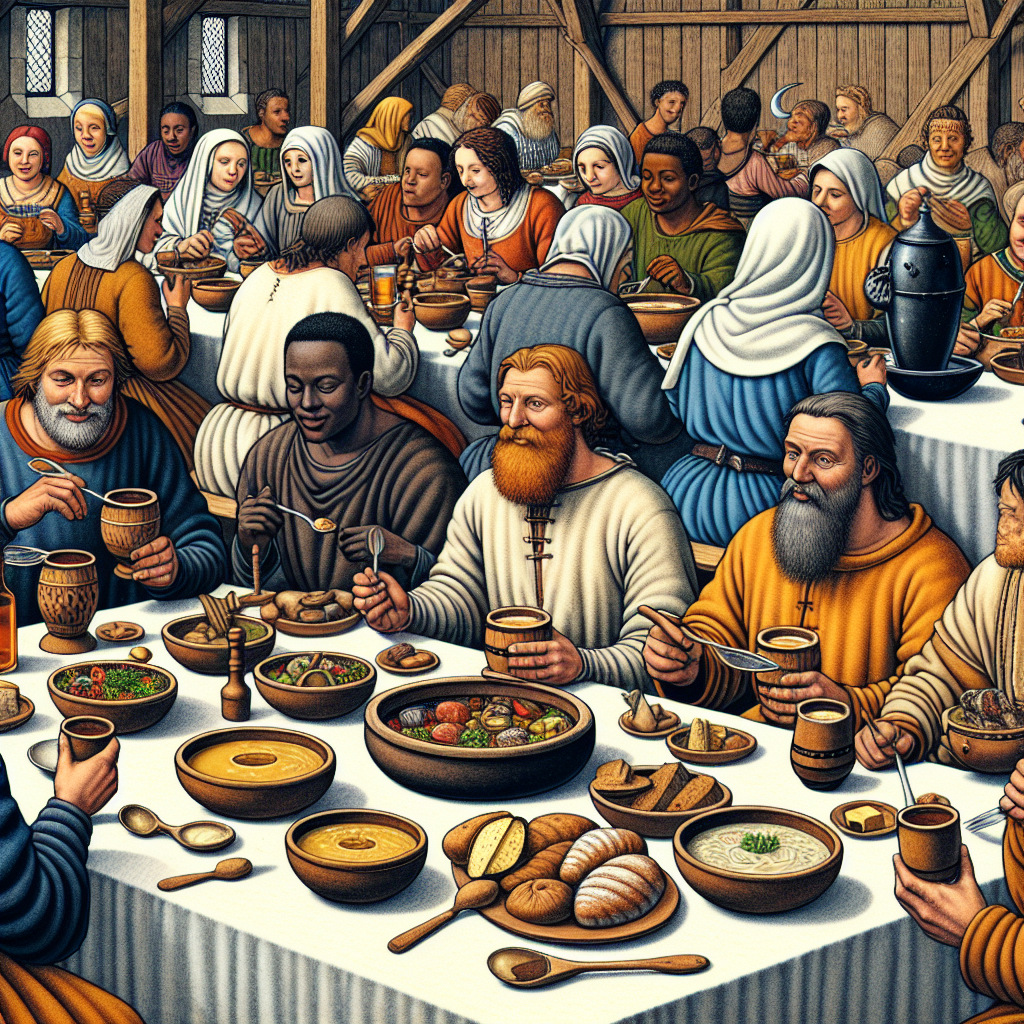

Before the plague, Europe’s economy was largely feudal — a rigid hierarchy where peasants worked the land for their lords in exchange for protection and basic subsistence. Labor was cheap and abundant, and social mobility was almost nonexistent. But when the Black Death struck between 1347 and 1351, the labor supply collapsed. Entire villages were abandoned. Fields went untilled. The few who survived suddenly found themselves in demand — and that simple shift in the balance between workers and employers triggered a revolution.

For the first time, peasants and artisans could demand higher wages and better conditions. Landowners, desperate to bring in their harvests, were forced to compete for labor. Some even began offering freedom from serfdom — a stunning reversal of centuries of social order. Governments tried to resist this change: England’s infamous Statute of Labourers of 1351, for example, made it illegal to pay workers more than pre-plague rates. But economic gravity could not be legislated away. Workers moved to towns, new industries emerged, and money began to circulate more freely.

The decline in population also had another, subtler effect — it increased the relative wealth of survivors. With fewer mouths to feed, inheritance became more common. Land, goods, and money flowed upward and outward, creating a new middle class of merchants and skilled tradespeople. This redistribution of wealth helped fuel the rise of consumer culture and urban economies. Towns like Florence, Venice, and London began to grow richer and more dynamic, laying the foundations for Renaissance commerce and finance.

Inflation also surged in the wake of the plague. With fewer goods being produced but more money in circulation, prices rose dramatically. For many, this was painful; but for traders and entrepreneurs, it opened opportunities. Banking houses — like the Medicis in Florence — began to play a greater role in managing and moving capital. The very idea of investment and profit, so crucial to capitalism, took firmer root in these years of economic chaos and adaptation.

Interestingly, the plague also spurred technological innovation. As the cost of labor rose, landowners and manufacturers looked for ways to make work more efficient. Mechanization began to appear in surprising places — from water-powered mills to improved looms and mining tools. This early wave of productivity foreshadowed the mindset that would one day drive the Industrial Revolution.

Moreover, the Black Death changed attitudes toward wealth and consumption. Before the plague, wealth was often viewed with suspicion, tied to sin and greed. But after witnessing the fragility of life, Europeans began to embrace the idea of enjoying the present — spending more on art, clothing, and comfort. In many ways, this shift in mentality helped fuel the cultural blossoming of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Even modern economists can trace certain fundamentals of today’s markets to that moment in history. The idea of wage negotiation, labor mobility, and even urban migration has its roots in the post-plague economic restructuring. Some historians argue that without the Black Death, Europe might have remained trapped in a stagnant feudal economy for centuries longer.

It’s a sobering paradox: one of humanity’s darkest chapters gave rise to many of the forces that define the modern world — from capitalism and innovation to individual economic agency. The Black Death taught societies that economies are not fixed systems but living organisms, capable of evolution and rebirth even after the most devastating collapse.

In a sense, the modern global economy was born not in the bustling markets of the Renaissance but in the silent, empty fields left behind by the plague. Out of loss came leverage, and out of death — an unexpected rebirth of human enterprise.