Superstitions might seem like relics of a more mystical past, yet even in a world guided by science and logic, they stubbornly persist. From athletes wearing “lucky socks” to students refusing to say “I’m ready” before an exam, these rituals are woven into human behavior across cultures and generations. The psychology behind superstitions reveals not foolishness, but something profoundly human — our need for control, comfort, and meaning in an unpredictable world.

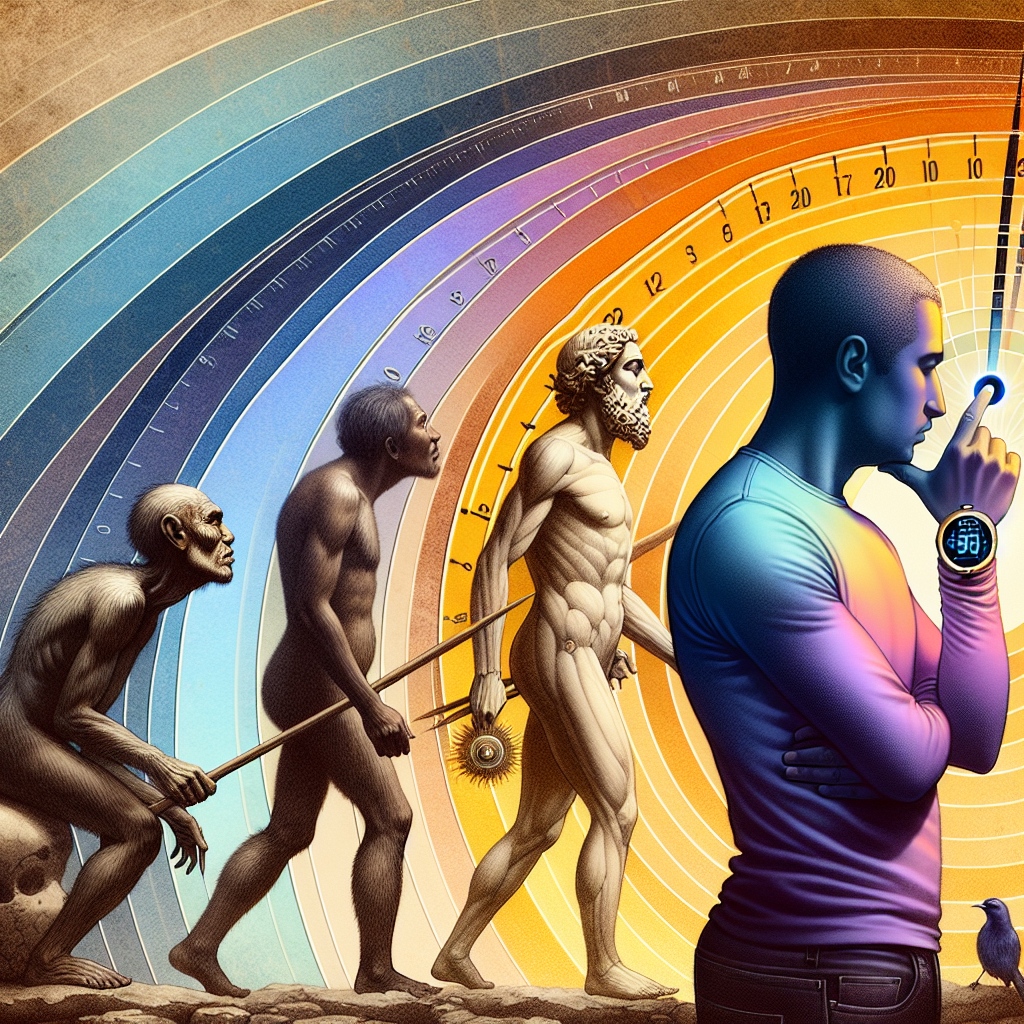

At its core, superstition arises from the mind’s pattern-seeking nature. Our brains are wired to find connections — even when they don’t exist. This is known as apophenia, the tendency to perceive patterns or causal relationships in random events. It’s the same cognitive quirk that makes us see faces in clouds or shapes in burnt toast. Thousands of years ago, this mental habit was adaptive: assuming the rustle in the grass was caused by a predator, even if it wasn’t, could save your life. Today, it makes us think that carrying a rabbit’s foot might somehow help us ace a job interview.

But superstition isn’t just about faulty reasoning. It’s deeply emotional. Psychologists have found that superstitious behavior spikes when people feel uncertain or anxious. In experiments, participants who were told their success depended partly on luck were more likely to engage in ritualistic behavior — like tapping the table or repeating phrases — than those told outcomes depended purely on skill. Essentially, superstitions give us an illusion of control. Even if knocking on wood can’t actually influence reality, the act itself reduces anxiety and boosts confidence, which can indirectly improve performance.

The power of belief also plays a role. The placebo effect, often associated with medicine, applies to rituals too. If you believe your “lucky charm” brings success, your body may respond as though it really does. Your posture straightens, your focus sharpens, and your confidence rises — all genuine psychological advantages born from an irrational source. Superstition, then, becomes a form of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Cultural history adds another layer. Many of the superstitions we follow today have surprisingly ancient origins. Knocking on wood, for example, dates back to pagan Europe, when trees were thought to house protective spirits. Crossing fingers for luck stems from early Christian symbolism, where intersecting fingers represented the power of the cross. Even something as seemingly modern as avoiding walking under ladders can be traced to medieval beliefs: the triangle formed by a ladder leaning against a wall symbolized the Holy Trinity, and breaking that shape was thought to invite misfortune.

Interestingly, superstitions adapt to modern life rather than disappear. We no longer fear black cats as omens of witchcraft, but we might still avoid posting bad news on Friday the 13th or hesitate to open an umbrella indoors. In Japan, the number 4 is unlucky because it sounds like the word for “death.” In Italy, it’s the number 17. Even technology isn’t immune: some people refuse to click “send” on important emails at 13:00 or will restart their computers three times for “good luck.”

Research also shows that superstitions can serve social and psychological functions beyond personal comfort. Shared rituals — like throwing coins into fountains or saying “break a leg” before a performance — create bonds between people, turning individual anxiety into collective reassurance. They’re cultural glue disguised as magic.

Ultimately, superstition reveals something paradoxical about human nature: our rationality depends on a bit of irrationality. We build rockets, cure diseases, and decode DNA, yet we still whisper small prayers before takeoff. It’s not that we believe the universe is controlled by luck, but that our emotions crave the illusion that it could be.

So the next time you find yourself avoiding a black cat or instinctively knocking on wood, don’t feel silly. You’re simply participating in one of humanity’s oldest coping mechanisms — a bridge between fear and faith, logic and hope. In a world full of uncertainty, a small ritual can make us feel, if only for a moment, that we have some say in our own fate.