Time feels like one of the most natural things in the world — we live by hours, seasons, and years, counting every tick and turn of our lives. But long before humans invented clocks or calendars, we had already developed an internal sense of time. It’s a remarkable adaptation, shaped not by machines or mathematics, but by biology, survival, and the rhythms of the natural world.

Our earliest ancestors didn’t know what a “minute” was, but they knew when to wake, when to hunt, and when to rest. The first sense of time came from the most reliable pattern in nature — the cycle of light and dark. Billions of years before humans even existed, life on Earth evolved internal rhythms known as circadian cycles, roughly matching the 24-hour rotation of the planet. These biological clocks govern when animals sleep, eat, and reproduce, and humans inherited this ancient mechanism. Every cell in our body still keeps time through proteins that rise and fall in predictable patterns, syncing us to the day.

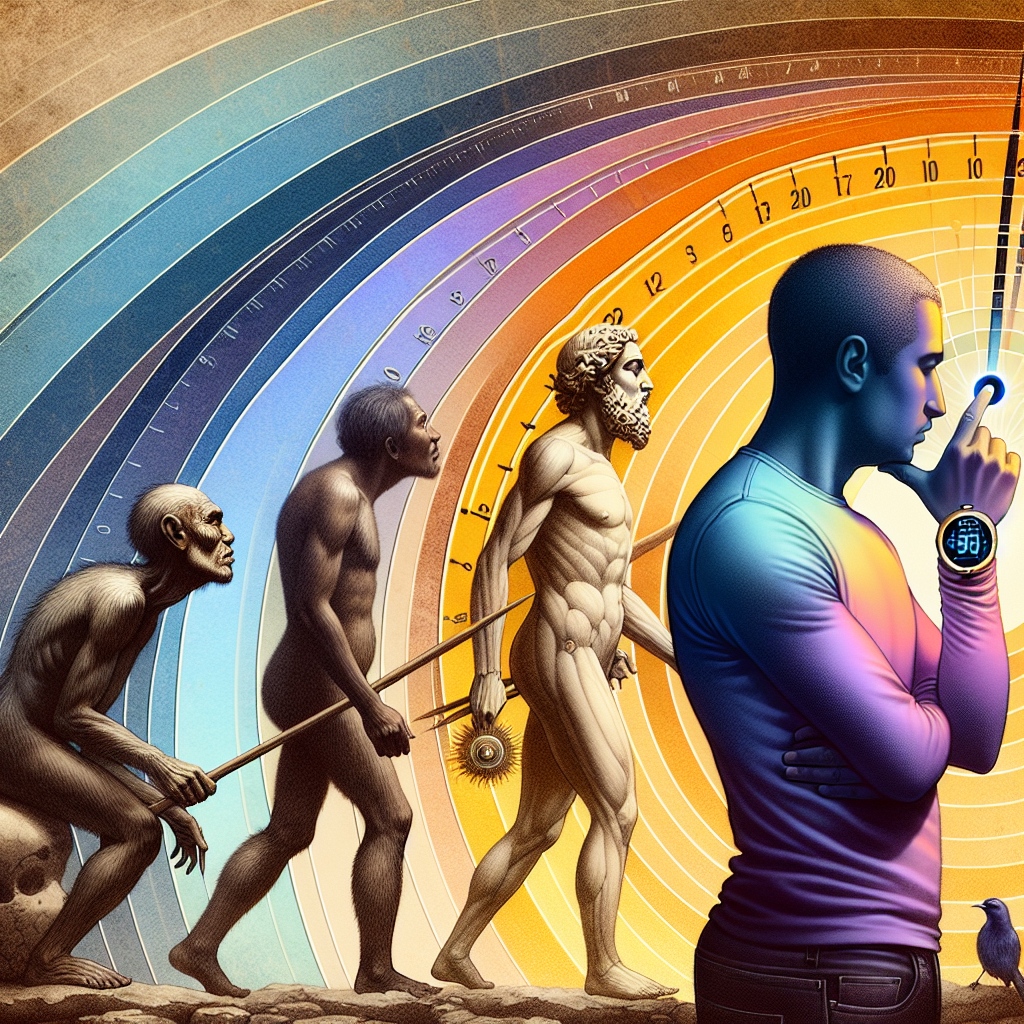

But beyond biology, humans developed something more abstract: an awareness of time’s passage. This was likely born from memory and anticipation — the ability to recall the past and imagine the future. These two mental powers, unique to humans, gave us a temporal consciousness. When early humans began storing food or planning hunts, they weren’t just reacting to the present — they were projecting themselves forward, understanding that later would come. This capacity for mental time travel transformed our species, allowing for agriculture, art, and civilization itself.

Interestingly, our sense of time isn’t uniform. A minute doesn’t always feel like a minute. Emotional intensity bends it: danger makes time feel slower, boredom stretches it, and joy collapses it. This elastic experience is a product of how the brain processes events. When something significant happens, we record more detail, and in retrospect, it feels as though it lasted longer. This is why a childhood summer seemed endless, while adult years blur together. The older we get, the fewer new experiences we encode — and so time seems to accelerate.

Even today, our internal clock is astonishingly accurate. In the absence of sunlight or watches, humans can maintain roughly consistent sleep-wake cycles. Yet, this natural rhythm can drift — a phenomenon known as free-running time. Experiments in which people lived underground without external cues showed that their “days” gradually stretched longer than 24 hours. This revealed that our sense of time isn’t perfectly fixed to the planet’s rotation but tuned closely enough to adapt through light exposure.

Culturally, our relationship with time has changed dramatically. Ancient peoples saw time as circular — a cycle of rebirth reflected in the stars, seasons, and agricultural rhythms. It was only later, especially with the rise of Christianity and industrial society, that humans began to see time as linear, moving from a clear beginning toward an end. Mechanical clocks, invented in the Middle Ages, intensified this perception, dividing life into measurable fragments. Suddenly, time was no longer something felt — it was something owned. The phrase “time is money” could only have existed once humanity began to measure life in hours worked and wages earned.

Yet despite our obsession with keeping time, our internal clocks still whisper older truths. Jet lag, shift work fatigue, and even seasonal depression all arise when modern schedules collide with the ancient rhythms our bodies still obey. We may have built cities that never sleep, but inside, we remain creatures of dawn and dusk.

What’s most fascinating is that time, as we perceive it, doesn’t exist “out there” — it’s a construct of the mind. Physically, the universe doesn’t distinguish between past and future; it’s our brains that impose order, sequencing events so we can make sense of cause and effect. Without this ability, consciousness itself would unravel into chaos. In a way, time is the scaffolding of awareness.

So when you glance at the clock and wonder where the day went, you’re not just tracking seconds — you’re experiencing the outcome of millions of years of evolution. Our sense of time is both ancient and deeply human: part biology, part memory, part imagination. It’s the quiet rhythm that holds our stories together — the heartbeat of existence itself.